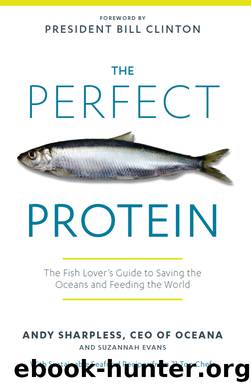

The Perfect Protein by Andy Sharpless

Author:Andy Sharpless

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Rodale

Published: 2013-04-16T04:00:00+00:00

TWO GREAT RIVERS zigzag to the Bering Sea from the mountains across Alaska’s western tundra. The Yukon and the Kuskokwim snake for thousands of switchbacked miles across a permafrost where a million tiny landlocked lakes appear in summer when the ice melts. This watershed is one of the world’s largest. In addition to caribou, moose, wolverines, grouse, ptarmigans, and mosquitoes, the Yukon–Kuskokwim (Y–K) Delta is home to all five North American species of Pacific salmon: coho, sockeye, pink, chum, and the largest—the king—chinook.

Twenty-five thousand people, mostly Yup’iks, live scattered across the treeless plains, and their connection to salmon goes back to their beginnings: The Yup’ik word for fish, neqa, also means “food.”

Myron Naneng’s office overlooks the Kuskokwim as it passes through Bethel, a town of 6,000 that serves as the hub for dozens of Yup’ik villages in this region 100 miles from the coast. Bethel feels much larger than it is. It’s home to the region’s only hospital and penitentiary. In winter, the town hosts a 300-mile dogsled race. The summer is filled with fishing.

Naneng is aggrieved. He is the president of the Association of Village Council Presidents, a nonprofit that represents the Yup’iks of the Y–K Delta. Now, several dozen of his constituents are facing $500 fines for fishing chinook from the Kuskokwim after the state government decided on an early closure for the spring run when the fish’s numbers failed to meet even low expectations. Chinook, which once supported a commercial fishery worth $10 million in the Y–K Delta, have been declining for years. The commercial fishery is gone. All that’s left are the subsistence fishermen, whose right to fish salmon is supposed to be protected under Alaska’s constitution.

Naneng, leaning back in his chair and knitting his hands across his belly, recounted a conversation he’d had 6 weeks earlier with Alaska governor Sean Parnell.

“I told him, ‘Governor, if someone asks me, “Should I go fishing today, I need to go out fishing for food,” what do you expect me to tell him?’ ” Naneng said, his voice quiet and firm. “He didn’t respond, so I said to him, ‘If anybody calls me and says, “Can I go out fishing today,” I will say go ahead and do it. “Nobody else is going to provide it for you.”’ And what did he do? [He said], ‘Oh, I’ll wait for a report from my staff from the fish biologist and all that before we’ll make a determination.’ He could have called them right there, the director of Fish and Game, open it so people can go out for food. And guess what happened. People went out for food and they got cited.”

During the closure, people were allowed to fish, but only with 6-inch mesh nets, which may catch smaller fish but allow the larger chinook to bounce out. Most people in villages and fish camps don’t have easy access to new equipment. At more than $1,000 for a 300-foot net with a float and lead line, new gear is prohibitively expensive for Yup’iks living off the water.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Automotive | Engineering |

| Transportation |

Whiskies Galore by Ian Buxton(41998)

Introduction to Aircraft Design (Cambridge Aerospace Series) by John P. Fielding(33122)

Small Unmanned Fixed-wing Aircraft Design by Andrew J. Keane Andras Sobester James P. Scanlan & András Sóbester & James P. Scanlan(32797)

Craft Beer for the Homebrewer by Michael Agnew(18238)

Turbulence by E. J. Noyes(8041)

The Complete Stick Figure Physics Tutorials by Allen Sarah(7366)

The Thirst by Nesbo Jo(6935)

Kaplan MCAT General Chemistry Review by Kaplan(6930)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(6615)

Modelling of Convective Heat and Mass Transfer in Rotating Flows by Igor V. Shevchuk(6434)

Learning SQL by Alan Beaulieu(6282)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6268)

Man-made Catastrophes and Risk Information Concealment by Dmitry Chernov & Didier Sornette(6012)

Digital Minimalism by Cal Newport;(5751)

Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence by Tegmark Max(5551)

iGen by Jean M. Twenge(5409)

Secrets of Antigravity Propulsion: Tesla, UFOs, and Classified Aerospace Technology by Ph.D. Paul A. Laviolette(5369)

Design of Trajectory Optimization Approach for Space Maneuver Vehicle Skip Entry Problems by Runqi Chai & Al Savvaris & Antonios Tsourdos & Senchun Chai(5066)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(4999)